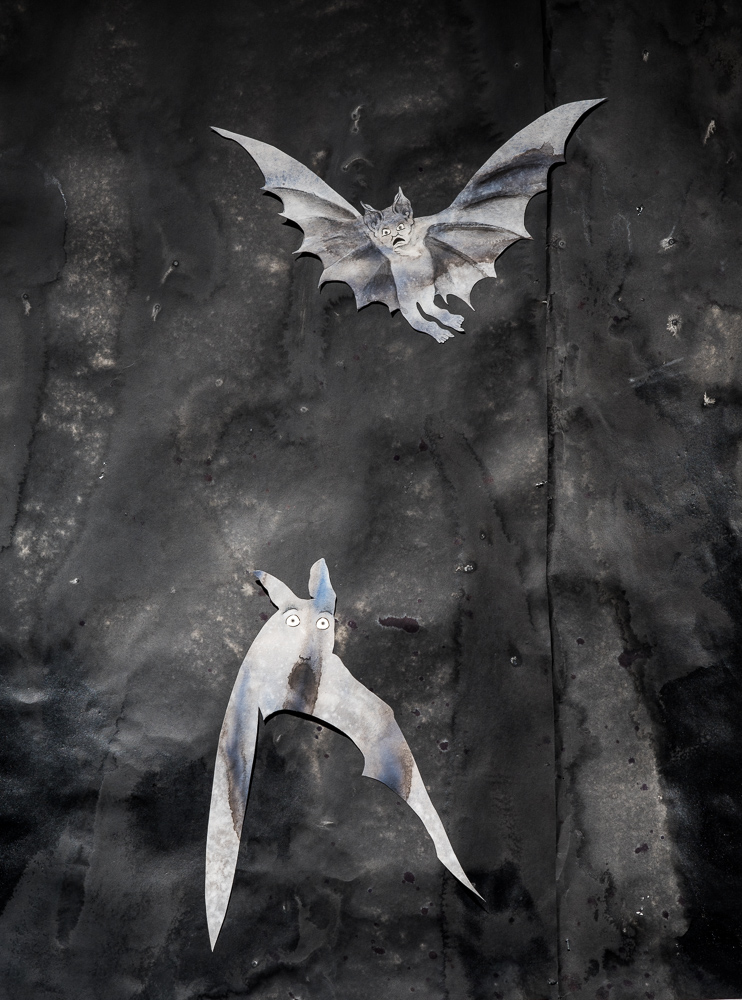

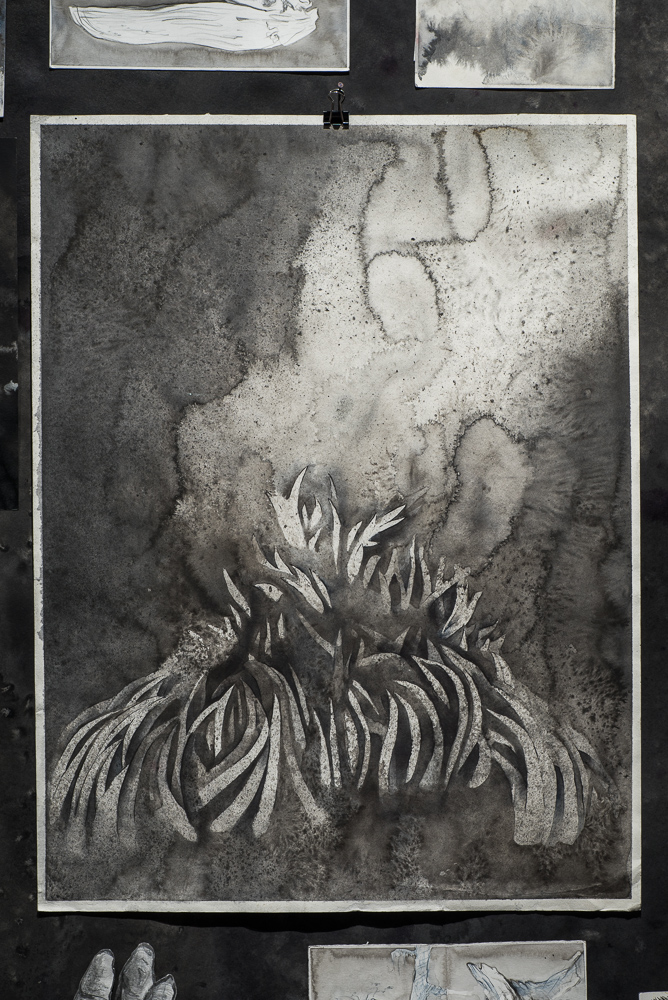

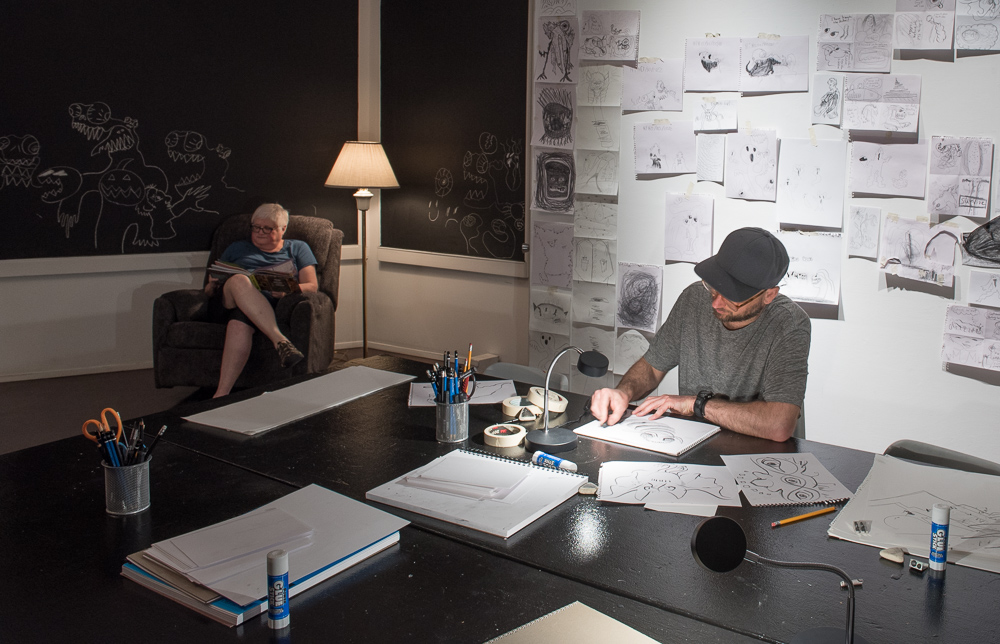

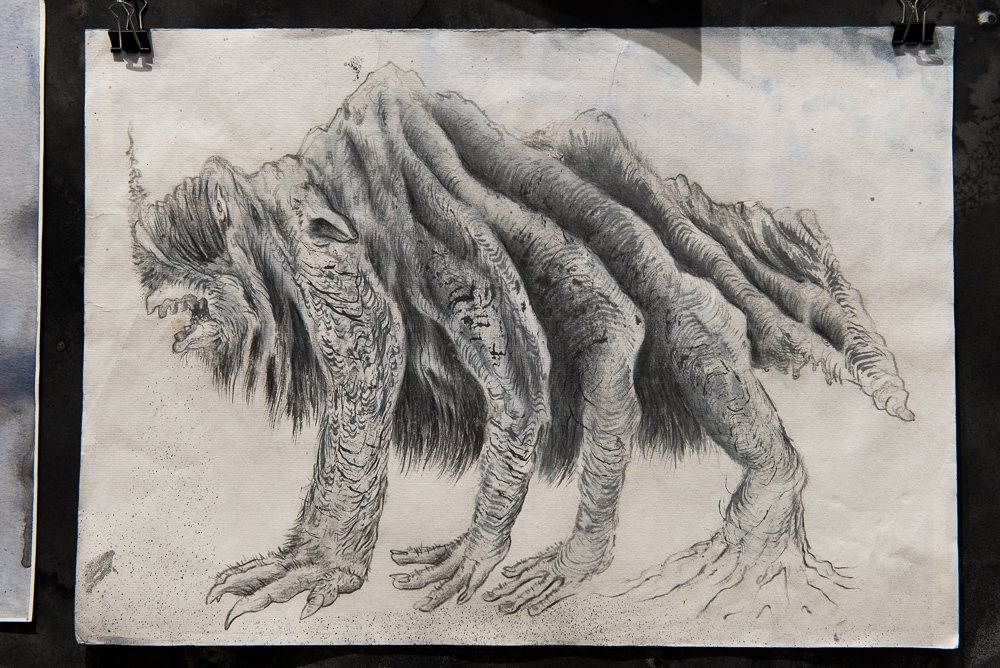

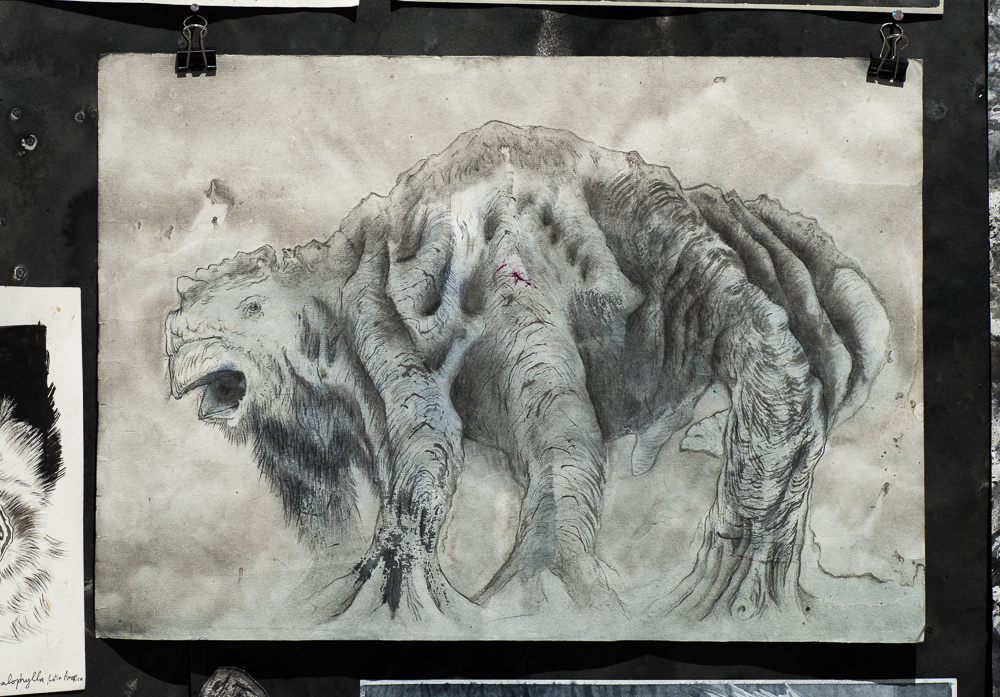

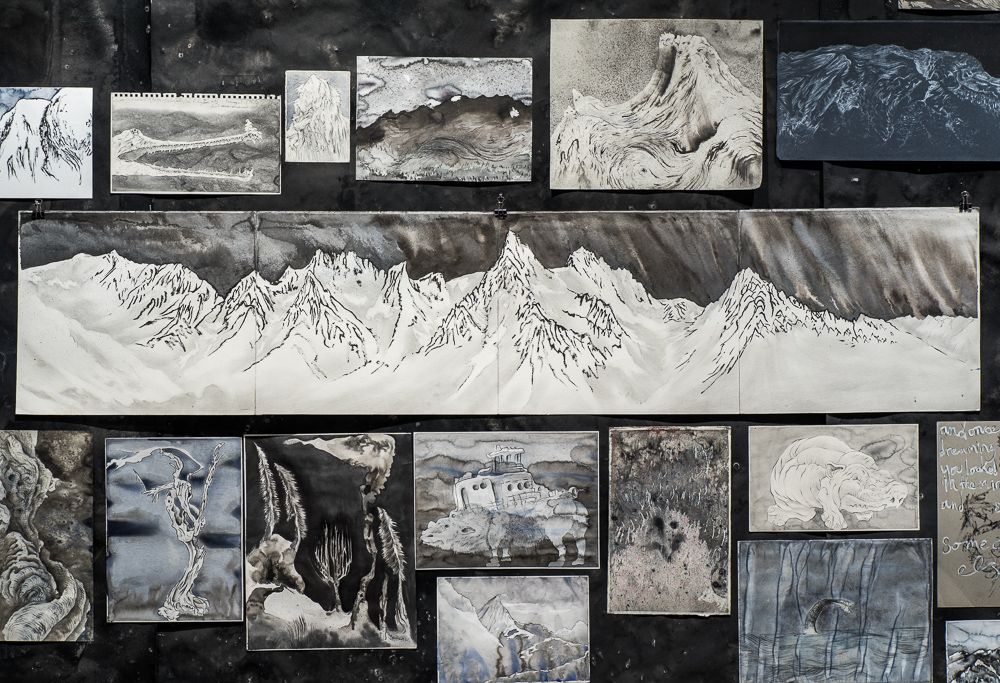

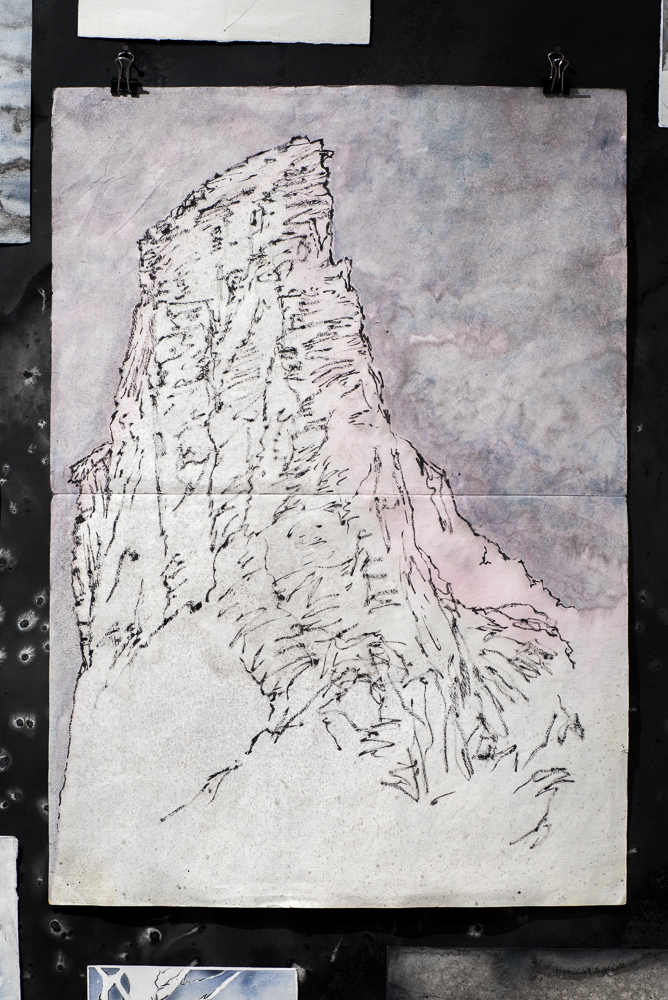

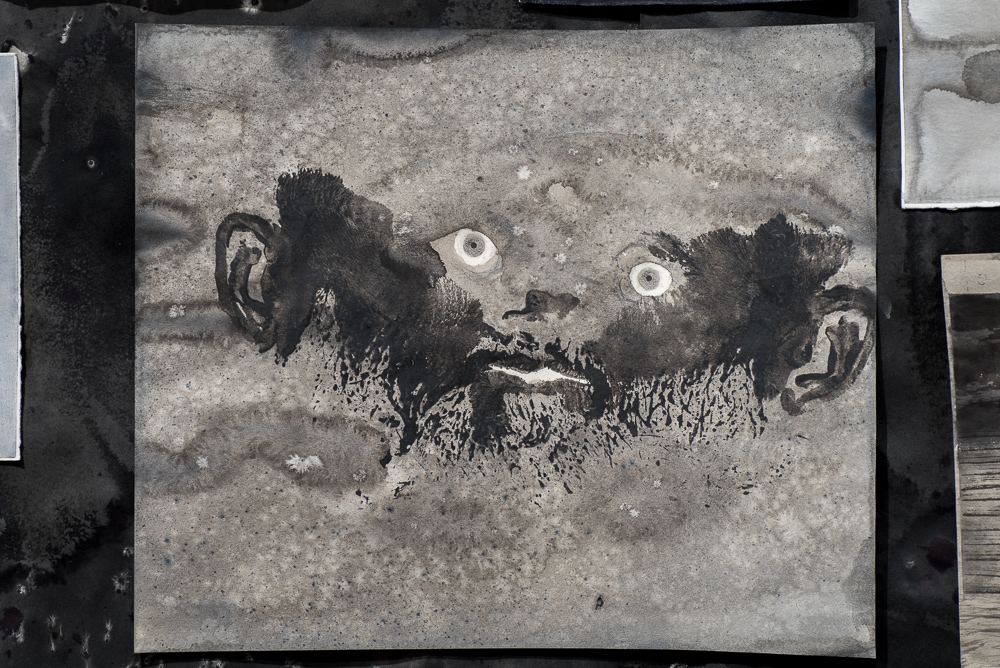

In the art exhibition Vestigial Trail, we take a journey through the complex imagination and eyes of Jim Holyoak. He is primarily a drawer, and he works mostly with ink and graphite on paper. Diversity is a key component in the scale and form of his work and how he undertakes his practice. He creates images that stretch from floor to ceiling, as well as small, intimate drawings. While Holyoak’s immense drawings are awesome — in the original sense of the word — he also scatters small details throughout the work that require close examination. A dark moodiness pervades many of his pieces, creating a sense of isolation. In others, he injects humour and play into the art. Creating from both observation and imagination, Holyoak inspects the boundaries of existing and fictitious worlds.

The frequent subjects of Holyoak’s artwork are two of his passions: mountains and monsters. In this exhibition, Holyoak considers the monstrous as it relates to our contemporary landscape. The exhibition’s title, Vestigial Trail, brings the two ideas together and is a play on the biomedical term “vestigial tail.” On occasion, humans are born with flesh protrusions from their lower backs or tailbones. These “tails” are often genetic hiccups — distal remnants of when our ancestors swung from trees. During the Victorian era, Charles Darwin cited human vestigial organs as support for his theory that humans are ancestral cousins to primates. At the same time, royals and the public were delighting in freak shows, which gave prominence to those born with physical anomalies, some of whom were considered monstrous, including conjoined twins, the Hottentot Venus, and people with extra appendages, such as vestigial tails.

The word “trail” in the title of Holyoak’s Vestigial Trail is a path that leads us from the coccyx into the deep, dark woods. It is a reminder not only of our evolution from animals, but an evolution with long roots into the Earth. According to both myth and science, the human body and the Earth share ancestry in the heavens. As astrophysicist Carl Sagan famously said on his popular television series, Cosmos, “The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of star stuff.” The Earth, the human body, and all plant and animal matter come from this original source. Indigenous knowledge tells us of our connection to the planet. “Okanagans teach that the body is Earth itself,” writes Okanagan author and educator Jeanette Armstrong. “Our flesh, blood, and bones are Earth-body; in all cycles in which Earth moves, so does our body.”

While Indigenous belief retains the connection to Earth, Judeo-Christian culture cut the genetic bond between land and humanity. In the Bible, Genesis (2:7) says that God formed Adam from “the dust of the ground.” Eve was not created from the Earth but from Adam’s rib. From the beginning, Eve was cast as the “other,” not the dominant. “Othering” is a process of separating, and it justifies creating a false hierarchy based on subjective criteria, whether it is race, language, culture, gender, ability, sexual orientation, species, or material form. In the story of Genesis, the snake tempts Eve, she bites the apple, and is cast out of paradise. At that moment, she is separated from the Earth. Who becomes the monster of the story: the snake or Eve? Monster Theory tells us monsters are born through the process of othering. Jerome Jeffrey Cohen, the father of Monster Theory, states that a monster “is always a displacement.” In Cohen’s essay “Monster Culture (Seven Theses),” where he reveals the nature of monsters and the monstrous, he states it is difficult to define monsters because one defining characteristic is that they don’t fit into categories; they can exist in reality and the imagination. In the current moment, which monster is scarier: the Demogorgon in Netflix’s Stranger Things series or Russian President Vladimir Putin?

Giving the example of vampires, Cohen also tells us a monster is born from our cultural fears and that we simultaneously fear and desire monsters. Canadian female impersonator Craig Russell (1948–1990) said in a 1978 interview, “I feel like Frankenstein sometimes, but everybody loves a monster.” As much as the “other” scares dominant culture, it is also the subject of fascination and curiosity.

In the Kootenays, we both love and fear the mountains. As places of play and wonder, the mountains can scare us when the weather turns wicked and the clouds roll in — we become cautious and wary of their power. As the Earth’s temperature rises and our forests burn, the monster comes down from the mountain to chase us and consume our homes. Each summer, as Cohen theorizes, the fire monster gets pushed back, only to return the next year. We can never kill it entirely.

For the exhibition Vestigial Trail, artist Jim Holyoak has transformed the gallery into an environment where our eyes and ears are invigorated and our imaginations thrive. It is both exciting and unsettling. Within the exhibition space, visitors have the chance to read, draw, and write. Through the processes of disturbance and reflection, can we remember that the mountain, the monster, the other are in fact ourselves? We can’t kill the monster entirely. Can we instead learn to witness, even embrace, our monstrous selves?

– Maggie Shirley is a poly-media artist and curator. Currently, she lives in the West Kootenay region of British Columbia where she is the curator at the Kootenay Gallery of Art in Castlegar. Shirley has curated a number of solo and group exhibitions, including Building the World We Want and The Hidden Hero Project. In 2021, she co-curated Overburden: Geology, Extraction and Metamorphosis in a Chaotic Age with Genevieve Roberston.

Photos by Jeremy Addington